“Big Cheese”

March 7, 2008 week #10

Photo: This reproduction of an 1848 wood-cut engraving of Colonel Thomas S. Meacham’s “Agricultural Hall” which became a health spa for a year or two after he died in 1847.

Who was Colonel Thomas Standish Meacham? His parents were Issac and Lucy (Standish) Meacham. His brothers John and Simon were among the first pioneers to the wilderness that was to become the Town of Sandy Creek. The title “Colonel” probably came from his drilling of troops on the village green. Colonel Meacham was elected as an assessor at the first town meeting for the Town of Sandy Creek in 1825 and later served as Associate Judge of Common Pleas for Oswego County from 1841-1845. Meacham is best known for the “Big Cheese” that was sent to President Andrew Jackson in 1835.

Colonel Meacham’s farm was on the Salt Road, about a mile from the Richland line in the Town of Sandy Creek. The buildings and dairy were considered the most pretentious and extensive in the township. The milk from this dairy was converted into cheese in his own factory.

Early in 1835 he had an idea that would bring fame to himself, the town and state in which he lived. His idea was to make the largest cheese ever produced in the state and send it to President Andrew Jackson. His plans were set in motion and by September of that year the preparations began. He hired a carpenter to build a special structure, containing a frame, hoops, and press several feet in diameter. The frame was lined with special cheese-cloth and for days the curd made from the milk on his 150 cow dairy farm was put into this frame. Each day the whey was squeezed out and the end product weighed 1,400 pounds. The cheese was boxed, sealed and ready for delivery to President Jackson in Washington.

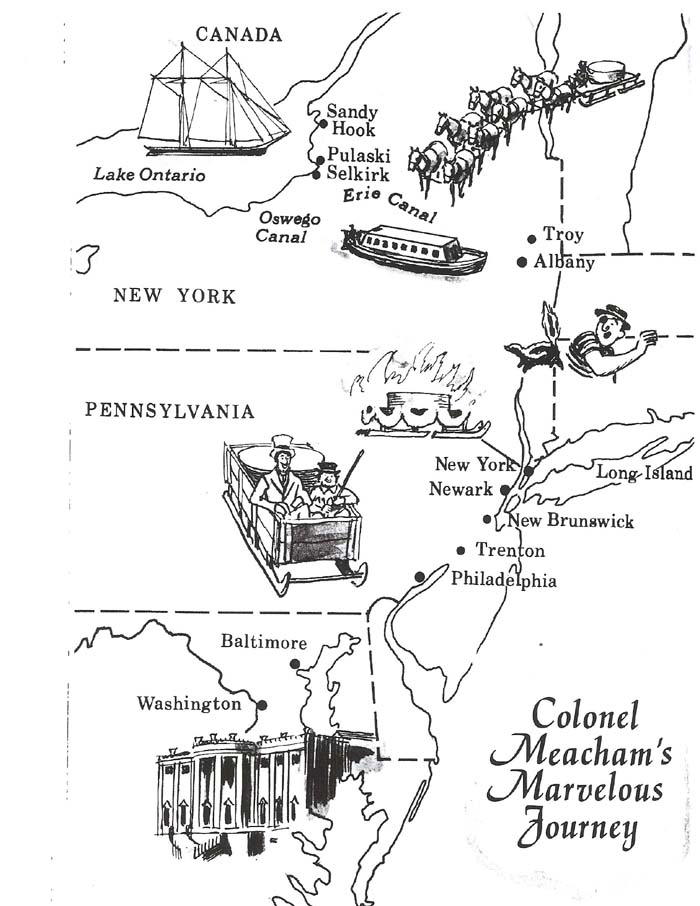

With a flare for the dramatic, he selected a large wagon which he had brightly painted and selected a team of forty-eight gray horses. The local residents joined the procession the day it started on its eventful journey. The procession reached Port Ontario by way of Pulaski and on November 15, 1835 it was loaded on a sailing vessel. As the Colonel stood on deck, a band played and cannons were fired. The trip to Washington began by way of Oswego, Syracuse, Albany and New York and the enthusiasm did not wane along the route. In due time it reached the Capital and was formally presented to the President of the United States in the name of the “Governor and the people of the State of New York and the Town of Sandy Creek.”

The “Big Cheese” was left in tact until February 22, 1836, when the President issued an invitation to all the people of the capital to “eat cheese.”

The Mark Twain of that day summoned his humor and wit to describe the occasion, published in a Washington newspaper: “This was Washington ’s Birthday and the President, the departments, the Senate, and we the people, have celebrated by eating the big cheese. The President’s house was thrown open, the multitude swarmed in. The Senate of the United States adjourned. The representatives of the various departments turned out. Representatives in swarms left the Capital…all for the purpose of eating cheese. Mr. Webster was here to eat cheese. Mr. Woodbury, Mr. Dickerson, Colonel Benton and the gallant Colonel Trowbridge were eating cheese. The court, the fashion, the beauty of Washington, were all eating cheese. Officers in Washington, foreign representatives in stars and garters; gay, gorgeous, joyous and dashing women, in all the pride and panoply and pomp of wealth, were eating cheese. Cheese…cheese…cheese…was on everybody’s lips and in everybody’s mouth. All you heard was cheese. All you saw was cheese. All you smelt was cheese. It was cheese, cheese, cheese. Streams of cheese were going up the avenue in everybody’s fists. Balls of cheese were in hundreds of pockets. Every handkerchief smelt of cheese. The whole atmosphere for a half a mile was infected and reeked of cheese.”

According to old account books kept by the Colonel and found many years later, the cost of making and delivering the cheese was $1200. Four more large cheeses, each of 700 pounds were manufactured and delivered to Vice-President Van Buren, Governor Marcy and the Mayors of New York City and Rochester.

This story can be found in a book written by Hayes Johnson, “The Working White House.”

|

White House Diary by Henrietta Nesbitt

FDR’s Housekeeper

Chapter 15 pages 203-204

When Andrew Jackson moved into the White House, following President Adams, he reported finding the East Room in a mess, and the furniture infested with every variety of bug, having been used for dozing by constituents waiting to see the President.

One holiday season soon after someone sent him a fourteen-hundred-pound cheese four feet across, and he had it set up in the East Room and cut there at a reception. I could have told “Old Hickory” that the best-brought-up people spill at receptions and trample what they spill, and naturally the Presidential cheese got trampled into the carpets and they say the smell didn’t come out for months.

I’ve always held President Jackson’s cheese responsible for attracting the grand-ancestors of many of our White House pests.

|

|

The White House Historical Association/White House History

When Henrietta Nesbitt (1874-1963) first saw the White House on March 4, 1933, she remarked that it resembled “a big wedding cake.” The day was Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first inauguration as president. The following day Nesbitt became the housekeeper at the White House. Although Mrs. Nesbitt, who was fifty-nine, had never worked as a professional housekeeper before, she was undaunted by the challenge. Her philosophy was that she had been keeping house all her life and it wouldn’t be any different at the White House, just on a larger scale. Little did Nesbitt know that she would spend more than a dozen years managing the nation’s busiest household during the trying times of the Great Depression and World War II.

Henrietta and her husband, Henry F. Nesbitt, had been neighbors of the Roosevelts in Hyde Park, New York. Eleanor Roosevelt and Nesbitt met through the formation of a local chapter of the League of Women Voters. Mrs. Roosevelt, heavily involved in her husband’s campaign for governor of New York, asked Nesbitt to make baked goods for the Roosevelt’s growing social functions at Hyde Park. When Franklin Roosevelt was elected to the White House in 1932, Mrs. Roosevelt asked both Nesbitts to work for them in the White House. Henry Nesbitt tracked the household accounts as chief steward. Two sets of books had to be kept as the government only paid for state dinners and receptions; all other meals were charged to the Roosevelts. After Henry Nesbitt’s death in 1938, Mrs. Nesbitt took over these duties with the help of an assistant.

Mrs. Nesbitt proved to be an indefatigable worker and her position involved not only care of the house, but oversight of the servants, meal planning, and the purchase of supplies from her command post on the ground floor of the historic residence. The Roosevelts were socially active and entertained over 10,000 persons during the 1937 season at the White House.

Nesbitt became a minor celebrity through her position and gave newspaper interviews about her menus. She also appeared on a radio program with other White House staffers to discuss the running of the presidential mansion. Her plain home-style meals were never widely appreciated at the White House and both President Roosevelt and visitors complained about the quality and variety of foods that were served. A 1937 New York Times article stated “any man might rebel against being served salt fish for luncheon four days in a row.” Roosevelt had a food rebellion the prior week and said that the “kitchen had better not send him any more liver for a while and he is also getting pretty tired of string beans.” Mrs. Nesbitt was aware that her menus were being discussed in the national news, but she excused it by saying that the president was stressed over world events. She also staunchly defended her uninspired menus by saying that the White House had to following rationing rules the same as everyone else. Eleanor Roosevelt ignored all criticism and remained loyal to Nesbitt. They both felt that the White House should be a model of food conservation efforts on the Home Front.

Mrs. Nesbitt remained on for a time at the White House after Harry S. Truman became president. However, Margaret Truman recounts in Bess W. Truman, that President Truman was served Brussels sprouts one too many times and Mrs. Nesbitt was summarily dismissed.

After leaving the White House, Mrs. Nesbitt wrote two books; White House Diary published in 1948 followed by The Presidential Cookbook: Feeding the Roosevelts and Their Guests in 1951. The diary is a chatty commentary of the dignitaries and heads of state that visited during her time there and provides an important glimpse of life behind the scenes at the Roosevelt White House.

|